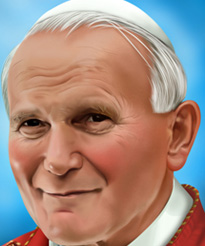

Intresting Facts About Pope John Paul II (Karol J. Wojtyla)

Saint of the day online, Saturday, October 22, 2017

21-10-2017

Saint Name: Pope John Paul II

Place: Wadowice

Birth: May 18, 1920

Death: 2 April 2005 (aged 84)

Feast: October 21

Papacy began: 16 October 1978

Papacy ended: 2 April 2005

Predecessor: John Paul I

Successor: Benedict XVI

Karol Wojtyla's journey began in Wadowice, about 25 miles southwest of Krakow in southern Poland, where he was born on May 18, 1920.

His father, also Karol, was a master tailor and a recruiting officer for the 12th Infantry Regiment of the Polish army. His mother was Emilia Kaczorowska, the convent-educated daughter of a packsaddle maker.

Young Karol grew up in simplicity, sometimes poverty, in a town shared by Catholics and Jews. The family lived in a second-floor apartment owned by a Jewish family. Nearby was St. Mary's, an eclectic 11-altar church with a bulbous black dome.

As a youth, Wojtyla swam in the Skawa River and was a devoted soccer goalie who often stopped to pray on his way home from school.

In 1929, just before he turned 9, his mother died of a heart and kidney ailment. He made his first Holy Communion the month she died. Three years later, his older brother, Edmund, a hospital intern, died of scarlet fever, contracted from a patient.

After his mother's death, Wojtyla would wake up at night to find his father on his knees, praying before the image of the Black Madonna of Czestochowa.

When Wojtyla was 18, he moved to Krakow with his father to study at Jagiellonian University. In summer 1939, Wojtyla completed military training with the Academic Legion. Two months later, on Sept. 1, 1939, Germany invaded Poland, and tanks reached Krakow five days later. The university was closed, and 184 professors were arrested and deported to a Nazi concentration camp.

Wojtyla continued his studies secretly and began underground activities, including performing in and writing plays steeped in Polish nationalism. Then, in February 1941, his father died. By the time he was 21, he had lost his entire family. The confluence of personal tragedy, his father's Catholic piety, and the influence of a remarkable Catholic layman would put Wojtyla on the road to the priesthood.

Shortly before his father's death, Wojtyla was drawn into religious life by a lay mystic, Jan Tyranowski. As the Nazis began arresting and deporting priests, Tyranowski organized and led the Living Rosary, a clandestine group of devout young Catholics. Wojtyla became one of its group leaders.

It was Tyranowski who introduced Wojtyla to the writings of St. John of the Cross, the 16th century Spanish theologian and mystic. St. John's idea of the "dark night of the soul" held that hardship, doubt and suffering purged the soul so that it could be filled by divine knowledge.

The asceticism of St. John of the Cross profoundly influenced Wojtyla's embrace of redemptive suffering. Like St. John himself and Poland's martyred St. Stanislaw, Wojtyla saw a kind of martyrdom in his own life. He took to heart the spiritual lessons he found in the sufferings of others and his own personal losses.

"His family tragedies inevitably shaped Wojtyla's character as a man and priest. He speaks of them often in private, especially of his poignant loneliness when his father died," Tad Szulc wrote in his biography of the pope. During the Nazi occupation, Wojtyla joined other Polish patriots in the "Rhapsodic Theater," which presented underground plays, including two that he wrote in 1940. They were performed in private homes to avoid the Gestapo, the Nazi secret police. His friends thought he was destined to become a great actor.

Wojtyla at that point had no thought of the priesthood. "I was completely absorbed by a passion for literature, especially for dramatic literature and for the theater," he recalled. But, as biographer Darcy O'Brien observed, his love of the dramatic was not a passing phase, but a portal. The war, the occupation of Poland by the Nazis and the sight of Jewish friends and neighbors forced from their homes to concentration camps moved Wojtyla to reconsider his future as an actor.

"To this day," he wrote in "Crossing the Threshold of Hope" (1995), "Auschwitz does not cease to admonish, reminding us that anti-Semitism is a great sin against humanity, that all racial hatred inevitably leads to the trampling of human dignity."

He began studying for the priesthood in a clandestine seminary in 1942 while keeping his job at a chemical plant to avoid raising Nazi suspicions. He also worked as a laborer in a rock quarry.

In 1944, the Gestapo made sweeps through the city, arresting young men, including seminarians, but Wojtyla avoided arrest. Later, a classmate was executed, and Wojtyla's name appeared on a Nazi death list. He eluded capture and continued his studies. He was ordained a priest, but did not join a specific order, on Nov. 1, 1946. At first, Wojtyla hoped to join the Carmelite Fathers, a religious order inspired by St. John of the Cross, whose monks go barefoot or wear sandals in keeping with Jesus' instruction not to burden themselves with possessions as they minister to others.

But his bishop sent him to Rome for graduate studies at the Pontifical Angelicum University, where Wojtyla earned a doctorate in ethics in 1948. He returned to Poland as a parish priest and began to write in earnest — poems, several books and more than 100 scholarly, reflective and philosophic articles. Wojtyla was unalterably devoted to God. Like his mentor, Tyranowski, and St. John of the Cross, his ecstatic meditation on the mystical "other" could carry him to a contemplative shore.

Decades later, he was still treading that shore as pope. Confidants and guests invited to join him in his private chapel in the Vatican reported that he became so focused in prayer that conscious thought seemed to recede, like a wave on a sandy beach, returning only as sighs and groans.

"He experiences God very, very intensely in prayer," said Cardinal Justin Rigali of Philadelphia. "It's very simple. Very, very profound." Wojtyla earned a doctorate in theology from Jagiellonian University in 1948. He taught moral theology at the church's seminary in Krakow in 1953, and became a professor of ethics and chairman of the philosophy department at Catholic University in Lublin in 1954.

In 1959, shortly after he was ordained auxiliary bishop of Krakow, he was named to the Polish Academy of Sciences in recognition of his work in philosophy. In 1964, he became archbishop of Krakow. In 1967, Pope Paul VI made Wojtyla, then 47, a cardinal. Wojtyla quickly earned a reputation within the highest circles of his church as a thinker and philosopher who stood up to communism and integrated traditional teachings with modernity. He was a major participant in the Second Vatican Council — joining in debates about religious freedom, modernity and liturgical reform — which aimed to bring the church into the modern world.

As archbishop of Krakow, Wojtyla had named a commission in 1966 to look at the issue of human sexuality, based in large part on his own pastoral experience counseling young people and couples. His commission's findings, which drew on modern clinical insights while preserving a Catholic moral framework, laid the groundwork for Humanae Vitae, the controversial encyclical issued by Pope Paul VI in 1968 that banned artificial birth control. Then in 1976, Wojtyla was invited to deliver what would be a much-hailed series of Lenten lectures on Christian humanism and God's love before the pope and ranking members of the Roman Curia. As a Cardinal, he also participated in the August 1978 conclave to choose a successor to Pope Paul VI. He was, therefore, no stranger to his fellow cardinals, who less than two months later gathered again in the Sistine Chapel again beneath Michelangelo's fresco of "The Last Judgment" to elect a successor to John Paul I after his sudden death. Just after dusk on Oct. 16, 1978, reportedly on the eighth ballot after a deadlock between two principal Italian candidates, the 58-year-old Wojtyla became the youngest pope in more than 120 years and the first non-Italian pope since Adrian VI of the Netherlands was elected in 1522.

Cardinal Wojtyla had a deep conviction of the importance of Pope Paul VI's Encyclical Letter Humanae Vitae, On Human Life, published in 1968. It was about more than the regulation of birth and issues of contraception; it was about the dignity of the human person and human love in the Divine Plan. Sadly, the letter became a rallying point for some who chose to dissent. However, Karol Cardinal Wojtyla's work in theological anthropology, his development of a theology of marriage and family, and his Wednesday Catechetical Instructions (later compiled as "Human Love in the Divine Plan" and popularly called the "Theology of the Body") as Pope, clearly built upon this important Encyclical letter of Paul VI and have ensured its lasting effects.

The death of Pope Paul VI on August 6, 1978, the Feast of the Transfiguration, brought Cardinal Wojtyla to Rome where he participated in the Conclave which elected Cardinal Albino Luciani of Venice as Pope. The gentle smiling Pope took the name John Paul I to represent his commitment to continuity with the pontificates of both of his predecessors and the Council which they presided over. Sadly, 33 days later Pope John Paul I died in office. 1978 then became the year of three Popes. Karol Cardinal Wojtyla soon heard the Lord call him to an assignment he probably never expected when he studied for the priesthood in an underground seminary in Poland.

On October 16, 1978, the Cardinals gathered under the guidance of the Holy Spirit and chose Karol Cardinal Wojtyla as the 263rd successor to the Apostle Peter. He took the name John Paul II as his first teaching act, sending the signal of continuity. He stepped out on to the balcony in St. Peters Square and proclaimed: "Be Not Afraid! Open up, no; swing wide the gates to Christ. Open up to his saving power the confines of the State, open up economic and political systems, the vast empires of culture, civilization and development... Be not afraid!"